The Life of Dr. Philip Jaisohn (1864-1951)

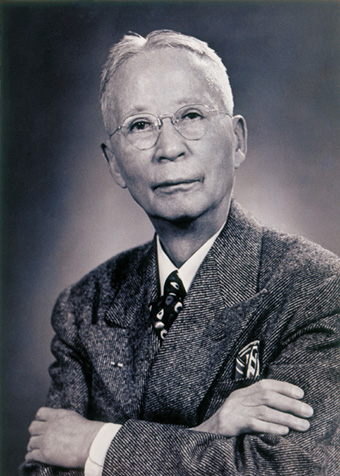

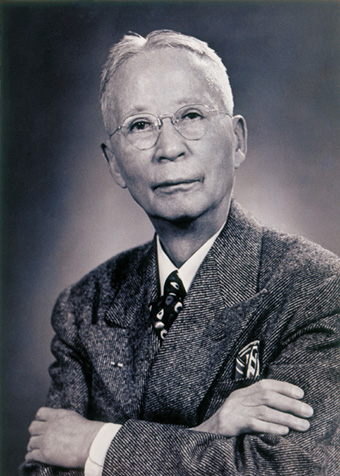

Dr. Philip Jaisohn, M.D., a man who left an indelible mark on Korean history as a pioneer and reformer, was born in 1864 at Kanae Village, Bosung county, near the southern tip of South Korea what was then known as the Hermit Kingdom. As a child, Dr. Jaisohn studied the Confucian classics and Chinese writing. At age 18, he became one of the youngest to pass the Civil Service Examinations, a rite of passage whose roots hearkened back to 8th century Korea, and beyond that to similar rites in imperial China. At age 19, he studied at the Youth Military Academy in Tokyo, Japan. Upon his return to Korea, he was appointed the commandant of Korean Military Academy. Two years later, in 1885, at age 21, he participated in a historic, unsuccessful coup against the government, the goal of which was to unmoor Korea from its feudalistic structures and begin rapid modernization. Its failure had profound consequences for Jaisohn and his clan. One of the more immediate results of the failure was that, along with two other young leaders, he became a fugitive in Japan for a brief time before he crossed the Pacific on a ship as a political refugee bound for San Francisco.

Dr. Philip Jaisohn, M.D., a man who left an indelible mark on Korean history as a pioneer and reformer, was born in 1864 at Kanae Village, Bosung county, near the southern tip of South Korea what was then known as the Hermit Kingdom. As a child, Dr. Jaisohn studied the Confucian classics and Chinese writing. At age 18, he became one of the youngest to pass the Civil Service Examinations, a rite of passage whose roots hearkened back to 8th century Korea, and beyond that to similar rites in imperial China. At age 19, he studied at the Youth Military Academy in Tokyo, Japan. Upon his return to Korea, he was appointed the commandant of Korean Military Academy. Two years later, in 1885, at age 21, he participated in a historic, unsuccessful coup against the government, the goal of which was to unmoor Korea from its feudalistic structures and begin rapid modernization. Its failure had profound consequences for Jaisohn and his clan. One of the more immediate results of the failure was that, along with two other young leaders, he became a fugitive in Japan for a brief time before he crossed the Pacific on a ship as a political refugee bound for San Francisco.

Arrival in America…

Upon arrival in the United States, Dr. Jaisohn was aided by the American industrialist John W. Hollenback who enabled him to pursue an academic course of study at the Hillman Academy in Wilkes-Barre, PA. His initial plan was to study law, but after working with Dr. Walter Reed of Washington, he enrolled instead at Columbian Medical College, now George Washington University. In 1892, Dr. Jaisohn became the first Korean ever to receive an American medical degree. (Two years earlier, he had been the first Korean to become a naturalized U.S. citizen.) Marriage followed in June of 1894: he wed Muriel Armstrong, a socialite and daughter of the U.S. Post Master General, and niece of President James Buchanan. It was the first interracial marriage on record between a Korean and an American in the U.S.

…and Return to his Beloved Korea

Concerned with the political future of his native land, Jaisohn returned to Korea in January of 1896. There he initiated another revolution, or rather, a series of reforms that eschewed violence in favor of more reliable but slower changes. These movements encompassed ventures in social, political, economic, and educational fields in addition to initiatives in medical and health care. Their effect in aggregate was to sow the seeds of democracy in Korea.

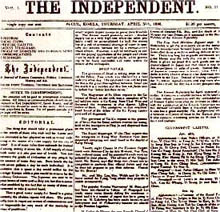

The Korean government offered Dr. Jaisohn high office as a minister, but he refused, and chose instead to channel his energies toward developing further reform movements, all of which were designed to stress the importance of democracy and the national independence of Korea. One of the most notable of these projects was the founding of the first Korean newspaper written in vernacular script, Han’gul. In contrast to the classical Chinese script that would have limited the newspaper’s readership only to the small circle of elites, the paper made it possible for women, children and many others from a wider stratum of society to access the information. April 7, 1896, the first publication date of The Independent, is observed today as the birthday of modern Korean journalism.

The Korean government offered Dr. Jaisohn high office as a minister, but he refused, and chose instead to channel his energies toward developing further reform movements, all of which were designed to stress the importance of democracy and the national independence of Korea. One of the most notable of these projects was the founding of the first Korean newspaper written in vernacular script, Han’gul. In contrast to the classical Chinese script that would have limited the newspaper’s readership only to the small circle of elites, the paper made it possible for women, children and many others from a wider stratum of society to access the information. April 7, 1896, the first publication date of The Independent, is observed today as the birthday of modern Korean journalism.

As a man in his thirties with dual ties to his native land and the U.S., Dr. Jaisohn also organized the Independence Club in Korea, through which he arranged for lectures and seminars. The forums that appeared under his auspices addressed questions of how best to modernize and democratize the country, while their participants received novel opportunities in leading open public discussions. On the site where Korean and Chinese figureheads had once met to underscore Korea’s subsidiary role as a tributary state of imperial China, Jaisohn oversaw the erection of a new structure, the Independence Gate, an attempt to inspire and assure Korean political sovereignty. He also worked as a teacher and the school where he taught, Paechae High School, produced numerous twentieth century Korean leaders, including the man who would become the first South Korean president.

Political Change brings Dr. Jaisohn back to America

The hurried departure of Dr. Jaisohn and his wife from Korea on May 14, 1898 involved a trick. The Korean government, alarmed by the sweeping political and social changes occurring in the country, staged a family emergency situation by using a fake telegram. The telegram stated that Dr. Jaisohn’s mother-in-law was at her death bed. The couple returned to the states by ship only to discover that the lady was in fine health. So this ended Dr. Jaisohn’s two year sojourn in Korea as an American citizen and a pioneer in Korean politics.

The hurried departure of Dr. Jaisohn and his wife from Korea on May 14, 1898 involved a trick. The Korean government, alarmed by the sweeping political and social changes occurring in the country, staged a family emergency situation by using a fake telegram. The telegram stated that Dr. Jaisohn’s mother-in-law was at her death bed. The couple returned to the states by ship only to discover that the lady was in fine health. So this ended Dr. Jaisohn’s two year sojourn in Korea as an American citizen and a pioneer in Korean politics.

Around the turn of the century, after Dr. Jaisohn made his return trip to the U.S. from Korea, imperialistic Japan became the sole military power in the Far East. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894, and Russo-Japanese War, fought in Manchuria and the East Sea in 1904, had cemented Japan’s victorious military position. In 1905, U.S. Defense Minister William Howard Taft and Japanese Prime Minister Katsura signed a secret agreement, whereby Japan agreed to refrain from attacking the Philippines in return for U.S. recognition of Japan’s right to have military control over the Korean peninsula. The agreement directly undermined the spirit of the peace treaty the U.S. had signed earlier with Korea in 1882, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce. Japan eventually annexed Korea in 1910.

The next twenty-five years of Dr. Jaisohn’s life in Pennsylvania were marked by entrepreneurship and continued dedication to Korean independence. His first employment upon his return to the states was with the Wistar Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1904, he started a stationary shop in Wilkes-Barre and Philadelphia, in collaboration with a friend and business partner Harold Deemer. A decade later, Philip Jaisohn and Company opened its doors at 17th and Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. It was a successful venture and the profits went to promote the Korean independence movement. On March 1, 1919, Koreans throughout the country rose up in a non-violent appeal for independence against the occupying power of Japan. The Japanese response was swift and brutal: 5,000 deaths and tens of thousands imprisoned and tortured. From April 16th to the19th of that same year, Jaisohn organized the historic First Korean Congress at the Little Theater on 1714 Delancey Street in Philadelphia. He also established the Korean Information Bureau and published the monthly journal Korean Review and founded the League of Friends of Korea, which were all organs dedicated to Korean independence. In 1925, his finances and attention strained by these political activities, he was forced to declare bankruptcy.

The next phase of Dr. Jaisohn’s life consisted most notably of his return to medical practice, a profession he embraced after a hiatus of nearly three decades. He borrowed money and took a year-long refresher course of study at the University of Pennsylvania. Between 1927 and 1936 he worked as a pathologist in several hospitals and published five excellent scientific articles. In 1936, Dr. Jaisohn opened his general practice in Chester, PA. For the next ten years, he continued to work in medicine and contributed articles to publications that had both Korean and American audiences. At the end of World War II, he was invited by the U.S. Military government in South Korea to be its Chief Advisor.

By the end of his life, Dr. Jaisohn could legitimately claim that he had served both his native land and adopted country honorably, the latter as diplomat and medical officer in three U.S. Wars – counting his work for the wounded in the Spanish American Civil War of 1898. Alongside earning the quieter good will from his Media neighbors, he was publicly recognized through commendations from Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman, and the U.S. Congress in 1946.

By the end of his life, Dr. Jaisohn could legitimately claim that he had served both his native land and adopted country honorably, the latter as diplomat and medical officer in three U.S. Wars – counting his work for the wounded in the Spanish American Civil War of 1898. Alongside earning the quieter good will from his Media neighbors, he was publicly recognized through commendations from Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman, and the U.S. Congress in 1946.

Dr. Jaisohn passed away on January 5, 1951, aged 87, in Norristown, PA. On April 2, 1994 Koreans in America bid him farewell as his ashes were delivered to Korea. The people of Korea heralded the arrival of his ashes at Kimpo Airport with emotion and, on April 8, 1994, his remains were permanently interred at the Korean National Cemetery.

Dr. Jaisohn was without doubt the founding father of modernization and democracy in the beloved land of his birth. The following words by Professor Chong-Sik Lee, dedicated to the memory of Dr. Philip Jaisohn, are etched in the marble monument at the Rose Tree Park in Media, PA, which was home to Dr. Jaisohn and his American family for the last twenty-five years of his life:

He loved his native land, Korea; shook it from its slumbers, roused the young and thundered at the old. In exile, he embraced his adopted country, served it with true devotion, healed the sick, and advanced science. But, he never forgot his native soil, spared no effort for her freedom. And, to the end of his life, he remained a dedicated champion of the cause of humanity everywhere.

The information compiled in this article is with thanks to Bong H. Hyun, M.D., D. Sc.

The Life of Dr. Philip Jaisohn (1864-1951)

Dr. Philip Jaisohn, M.D., a man who left an indelible mark on Korean history as a pioneer and reformer, was born in 1864 at Kanae Village, Bosung county, near the southern tip of South Korea what was then known as the Hermit Kingdom. As a child, Dr. Jaisohn studied the Confucian classics and Chinese writing. At age 18, he became one of the youngest to pass the Civil Service Examinations, a rite of passage whose roots hearkened back to 8th century Korea, and beyond that to similar rites in imperial China. At age 19, he studied at the Youth Military Academy in Tokyo, Japan. Upon his return to Korea, he was appointed the commandant of Korean Military Academy. Two years later, in 1885, at age 21, he participated in a historic, unsuccessful coup against the government, the goal of which was to unmoor Korea from its feudalistic structures and begin rapid modernization. Its failure had profound consequences for Jaisohn and his clan. One of the more immediate results of the failure was that, along with two other young leaders, he became a fugitive in Japan for a brief time before he crossed the Pacific on a ship as a political refugee bound for San Francisco.

Arrival in America…

Upon arrival in the United States, Dr. Jaisohn was aided by the American industrialist John W. Hollenback who enabled him to pursue an academic course of study at the Hillman Academy in Wilkes-Barre, PA. His initial plan was to study law, but after working with Dr. Walter Reed of Washington, he enrolled instead at Columbian Medical College, now George Washington University. In 1892, Dr. Jaisohn became the first Korean ever to receive an American medical degree. (Two years earlier, he had been the first Korean to become a naturalized U.S. citizen.) Marriage followed in June of 1894: he wed Muriel Armstrong, a socialite and daughter of the U.S. Post Master General, and niece of President James Buchanan. It was the first interracial marriage on record between a Korean and an American in the U.S.

…and Return to his Beloved Korea

Concerned with the political future of his native land, Jaisohn returned to Korea in January of 1896. There he initiated another revolution, or rather, a series of reforms that eschewed violence in favor of more reliable but slower changes. These movements encompassed ventures in social, political, economic, and educational fields in addition to initiatives in medical and health care. Their effect in aggregate was to sow the seeds of democracy in Korea.

The Korean government offered Dr. Jaisohn high office as a minister, but he refused, and chose instead to channel his energies toward developing further reform movements, all of which were designed to stress the importance of democracy and the national independence of Korea. One of the most notable of these projects was the founding of the first Korean newspaper written in vernacular script, Han’gul. In contrast to the classical Chinese script that would have limited the newspaper’s readership only to the small circle of elites, the paper made it possible for women, children and many others from a wider stratum of society to access the information. April 7, 1896, the first publication date of The Independent, is observed today as the birthday of modern Korean journalism.

As a man in his thirties with dual ties to his native land and the U.S., Dr. Jaisohn also organized the Independence Club in Korea, through which he arranged for lectures and seminars. The forums that appeared under his auspices addressed questions of how best to modernize and democratize the country, while their participants received novel opportunities in leading open public discussions. On the site where Korean and Chinese figureheads had once met to underscore Korea’s subsidiary role as a tributary state of imperial China, Jaisohn oversaw the erection of a new structure, the Independence Gate, an attempt to inspire and assure Korean political sovereignty. He also worked as a teacher and the school where he taught, Paechae High School, produced numerous twentieth century Korean leaders, including the man who would become the first South Korean president.

Political Change brings Dr. Jaisohn back to America

The hurried departure of Dr. Jaisohn and his wife from Korea on May 14, 1898 involved a trick. The Korean government, alarmed by the sweeping political and social changes occurring in the country, staged a family emergency situation by using a fake telegram. The telegram stated that Dr. Jaisohn’s mother-in-law was at her death bed. The couple returned to the states by ship only to discover that the lady was in fine health. So this ended Dr. Jaisohn’s two year sojourn in Korea as an American citizen and a pioneer in Korean politics.

Around the turn of the century, after Dr. Jaisohn made his return trip to the U.S. from Korea, imperialistic Japan became the sole military power in the Far East. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894, and Russo-Japanese War, fought in Manchuria and the East Sea in 1904, had cemented Japan’s victorious military position. In 1905, U.S. Defense Minister William Howard Taft and Japanese Prime Minister Katsura signed a secret agreement, whereby Japan agreed to refrain from attacking the Philippines in return for U.S. recognition of Japan’s right to have military control over the Korean peninsula. The agreement directly undermined the spirit of the peace treaty the U.S. had signed earlier with Korea in 1882, the Treaty of Amity and Commerce. Japan eventually annexed Korea in 1910.

The next twenty-five years of Dr. Jaisohn’s life in Pennsylvania were marked by entrepreneurship and continued dedication to Korean independence. His first employment upon his return to the states was with the Wistar Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1904, he started a stationary shop in Wilkes-Barre and Philadelphia, in collaboration with a friend and business partner Harold Deemer. A decade later, Philip Jaisohn and Company opened its doors at 17th and Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. It was a successful venture and the profits went to promote the Korean independence movement. On March 1, 1919, Koreans throughout the country rose up in a non-violent appeal for independence against the occupying power of Japan. The Japanese response was swift and brutal: 5,000 deaths and tens of thousands imprisoned and tortured. From April 16th to the19th of that same year, Jaisohn organized the historic First Korean Congress at the Little Theater on 1714 Delancey Street in Philadelphia. He also established the Korean Information Bureau and published the monthly journal Korean Review and founded the League of Friends of Korea, which were all organs dedicated to Korean independence. In 1925, his finances and attention strained by these political activities, he was forced to declare bankruptcy.

The next phase of Dr. Jaisohn’s life consisted most notably of his return to medical practice, a profession he embraced after a hiatus of nearly three decades. He borrowed money and took a year-long refresher course of study at the University of Pennsylvania. Between 1927 and 1936 he worked as a pathologist in several hospitals and published five excellent scientific articles. In 1936, Dr. Jaisohn opened his general practice in Chester, PA. For the next ten years, he continued to work in medicine and contributed articles to publications that had both Korean and American audiences. At the end of World War II, he was invited by the U.S. Military government in South Korea to be its Chief Advisor.

By the end of his life, Dr. Jaisohn could legitimately claim that he had served both his native land and adopted country honorably, the latter as diplomat and medical officer in three U.S. Wars – counting his work for the wounded in the Spanish American Civil War of 1898. Alongside earning the quieter good will from his Media neighbors, he was publicly recognized through commendations from Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman, and the U.S. Congress in 1946.Dr. Jaisohn passed away on January 5, 1951, aged 87, in Norristown, PA. On April 2, 1994 Koreans in America bid him farewell as his ashes were delivered to Korea. The people of Korea heralded the arrival of his ashes at Kimpo Airport with emotion and, on April 8, 1994, his remains were permanently interred at the Korean National Cemetery.Dr. Jaisohn was without doubt the founding father of modernization and democracy in the beloved land of his birth. The following words by Professor Chong-Sik Lee, dedicated to the memory of Dr. Philip Jaisohn, are etched in the marble monument at the Rose Tree Park in Media, PA, which was home to Dr. Jaisohn and his American family for the last twenty-five years of his life:

He loved his native land, Korea; shook it from its slumbers, roused the young and thundered at the old. In exile, he embraced his adopted country, served it with true devotion, healed the sick, and advanced science. But, he never forgot his native soil, spared no effort for her freedom. And, to the end of his life, he remained a dedicated champion of the cause of humanity everywhere.

The information compiled in this article is with thanks to Bong H. Hyun, M.D., D. Sc.

PHILADELPHIA OFFICE

6705 Old York Rd.

Philadelphia, PA 19126

215-224-2000

LANSDALE OFFICE

51 Medical Campus Dr.

Lansdale, PA 19446

215-997-2101

THE PHILIP JAISOHN MEMORIAL HOUSE

100 E Lincoln St.

Media, PA 19063

610-627-9768

© 2020 The Philip Jaisohn Memorial Foundation. All Rights Reserved.